Harris's Sparrow

General Description

The Harris's Sparrow is the largest sparrow in North America. In breeding plumage, it has a black crown, chin, and upper breast, with gray cheeks and a clear white belly. Its back and wings are heavily streaked, and its bill is pink. Adults in non-breeding plumage have brown rather than gray cheeks. Juveniles are similar in appearance to non-breeding adults, but lack the black face and head.

Habitat

Harris's Sparrows nest in stunted boreal forests, where the northern forest and tundra meet. In winter, they inhabit brushy areas in open woodlands. During migration, they can be seen at woodland edges, in brushy thickets, hedgerows, and shelterbelts.

Behavior

Harris's Sparrows will flock in late summer before migration starts. They sometimes flock with other species, especially other sparrows and Dark-eyed Juncos. In winter, these flocks feed on the ground near brushy places and will fly up to the tops of thickets when they are disturbed.

Diet

During the fall, winter, and spring, Harris's Sparrows eat mostly plant matter, including seeds, berries, flowers, and spruce needles. In summer, they also eat insects and other arthropods.

Nesting

The male defends a territory and attracts a mate by singing. Males and females generally arrive on the breeding grounds at the same time, and monogamous pairs form soon after their arrival. The nest is located in a small depression on the ground on a small hummock, hidden under a birch, alder, spruce, or other shrub or small tree. The female builds the nest, which is an open cup of lichen, moss, and twigs, lined with fine grass and hair. The female incubates 3-5 eggs for 12-14 days. Both parents help feed the young, which leave the nest 8-10 days after hatching. The young cannot fly when they fledge, but start to fly short distances about four days after fledging. The parents continue to feed the young for about two weeks after fledging.

Migration Status

Harris's Sparrows leave the nesting area by early September and travel slowly to wintering grounds, arriving mostly in November. They winter in the central Great Plains region from South Dakota to Texas. They start moving north at the end of February, but the bulk of the population doesn't arrive on the breeding grounds until late April or early May.

Conservation Status

Harris's Sparrows' breeding grounds are very remote; the first nest was not discovered until 1931. This remoteness protects them from human development, and they are quite common within their range. Habitat loss due to fire and the effects of global warming are potential threats. During the 20th Century, they may have expanded their wintering range, perhaps due to feeding stations and the establishment of winter wheat crops in some areas. However, this may actually reflect increased observation levels and more complete information rather than an actual increase. The Harris's Sparrow does not appear in Dawson and Bowles' (1909) book on Washington birds, which may be because they were less common, or because there were fewer people looking for them.

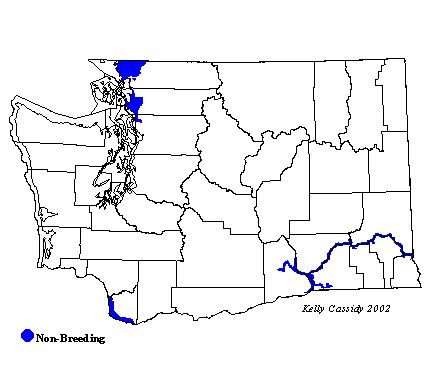

When and Where to Find in Washington

The Harris's Sparrow is a rare but regular wintering bird in Washington. Although they are more common on the Canadian side, they have shown up on about half of the Christmas Bird Counts in the Okanogan Valley and about 20% of the counts in Spokane. About 70% of Bellingham's Christmas Bird Counts have found a few Harris's Sparrows. Throughout the rest of western Washington, they are rare, with a few sightings reported each winter, from October through early May.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | ||||||||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | R | R | R | |||||||||

| Okanogan | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | |||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R | R | R | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Green-tailed TowheePipilo chlorurus

Green-tailed TowheePipilo chlorurus Spotted TowheePipilo maculatus

Spotted TowheePipilo maculatus American Tree SparrowSpizella arborea

American Tree SparrowSpizella arborea Chipping SparrowSpizella passerina

Chipping SparrowSpizella passerina Clay-colored SparrowSpizella pallida

Clay-colored SparrowSpizella pallida Brewer's SparrowSpizella breweri

Brewer's SparrowSpizella breweri Vesper SparrowPooecetes gramineus

Vesper SparrowPooecetes gramineus Lark SparrowChondestes grammacus

Lark SparrowChondestes grammacus Black-throated SparrowAmphispiza bilineata

Black-throated SparrowAmphispiza bilineata Sage SparrowAmphispiza belli

Sage SparrowAmphispiza belli Lark BuntingCalamospiza melanocorys

Lark BuntingCalamospiza melanocorys Savannah SparrowPasserculus sandwichensis

Savannah SparrowPasserculus sandwichensis Grasshopper SparrowAmmodramus savannarum

Grasshopper SparrowAmmodramus savannarum Le Conte's SparrowAmmodramus leconteii

Le Conte's SparrowAmmodramus leconteii Nelson's Sharp-tailed SparrowAmmodramus nelsoni

Nelson's Sharp-tailed SparrowAmmodramus nelsoni Fox SparrowPasserella iliaca

Fox SparrowPasserella iliaca Song SparrowMelospiza melodia

Song SparrowMelospiza melodia Lincoln's SparrowMelospiza lincolnii

Lincoln's SparrowMelospiza lincolnii Swamp SparrowMelospiza georgiana

Swamp SparrowMelospiza georgiana White-throated SparrowZonotrichia albicollis

White-throated SparrowZonotrichia albicollis Harris's SparrowZonotrichia querula

Harris's SparrowZonotrichia querula White-crowned SparrowZonotrichia leucophrys

White-crowned SparrowZonotrichia leucophrys Golden-crowned SparrowZonotrichia atricapilla

Golden-crowned SparrowZonotrichia atricapilla Dark-eyed JuncoJunco hyemalis

Dark-eyed JuncoJunco hyemalis Lapland LongspurCalcarius lapponicus

Lapland LongspurCalcarius lapponicus Chestnut-collared LongspurCalcarius ornatus

Chestnut-collared LongspurCalcarius ornatus Rustic BuntingEmberiza rustica

Rustic BuntingEmberiza rustica Snow BuntingPlectrophenax nivalis

Snow BuntingPlectrophenax nivalis McKay's BuntingPlectrophenax hyperboreus

McKay's BuntingPlectrophenax hyperboreus