Great Blue Heron

General Description

The familiar Great Blue Heron is the largest heron in North America. It is a large bird, with a slate-gray body, chestnut and black accents, and very long legs and neck. In flight, it looks enormous, with a six-foot wingspan. Adults sport a shaggy ruff at the base of their necks. A black eyebrow extends back to black plumes emerging from the head. Juveniles have a dark crown with no plumes or ruff, and a mottled neck. In flight, a Great Blue Heron typically holds its head in toward its body with its neck bent.

Habitat

Adaptable and widespread, the Great Blue Heron is found in a wide variety of habitats. When feeding, it is usually seen in slow-moving or calm salt, fresh, or brackish water. Great Blue Herons inhabit sheltered, shallow bays and inlets, sloughs, marshes, wet meadows, shores of lakes, and rivers. Nesting colonies are typically found in mature forests, on islands, or near mudflats, and do best when they are free of human disturbance and have foraging areas close by.

Behavior

Great Blue Herons are often seen flying high overhead with slow wing-beats. When foraging, they stand silently along riverbanks, lake shores, or in wet meadows, waiting for prey to come by, which they then strike with their bills. They will also stalk prey slowly and deliberately. Although they hunt predominantly by day, they may also be active at night. They are solitary or small-group foragers, but they nest in colonies. Males typically choose shoreline areas for foraging, and females and juveniles forage in more upland areas.

Diet

The variable diet of Great Blue Herons allows them to exploit a variety of habitats. This adaptability also enables them to winter farther north than most herons. Fish, amphibians, reptiles, invertebrates, small mammals, and even other birds are all potential prey of the Great Blue Heron. In Washington, much of their winter hunting is on land, with voles making up a major portion of their winter diet.

Nesting

Great Blue Herons usually breed in colonies containing a few to several hundred pairs. Isolated pair-breeding is rare. Nest building begins in February when a male chooses a nesting territory and displays to attract a female. The nest is usually situated high up in a tree. The male gathers sticks for the female who fashions them into a platform nest lined with small twigs, bark strips, and conifer needles. Both parents incubate the 3-5 eggs for 25-29 days. Both parents regurgitate food for the young. The young can first fly at about 60 days old, although they continue to return to the nest and are fed by the adults for another few weeks. Pair bonds only last for the nesting season, and adults form new bonds each year.

Migration Status

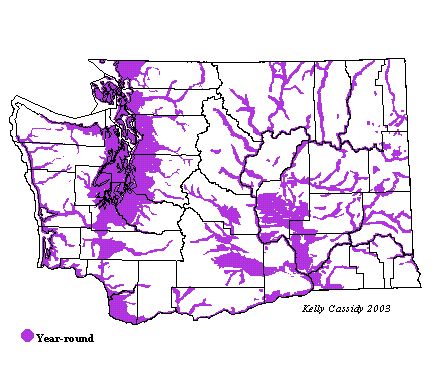

In parts of their range where food is not available in the winter, Great Blue Herons are migratory, and some may migrate to Washington from points farther north. Most of Washington's breeding population remains in the state year round. In parts of eastern Washington where the water freezes, Great Blue Heron populations concentrate along major rivers where food is available, or they hunt rodents on land.

Conservation Status

This highly adaptable species thrives in a wide variety of habitats over a broad range. Although Great Blue Herons are common and widespread, disturbance during a breeding season may lead to nest failure or colony abandonment. In April of 1999, 40% of the Seattle-area heron colonies were abandoned mid-season. This may have been caused by human disturbance or, as has recently observed in the Seattle area, by avaian predators. Bald Eagles, becoming increasingly more common with increasingly less foraging habitat, have taken to harassing Great Blue Herons on their colonies and feeding on the chicks. Adding to the impact, crows now wait on the sidelines and swoop in to take the remaining eggs once the eagles finish their meals. Another form of disturbance that is detrimental to herons on nesting colonies is noise. Clear-cutting and construction near a colony are particularly damaging, and a 1000-foot buffer zone around colonies is recommended. One change that has been noticed in Washington in recent years is that colonies that once numbered 100-200 nests are breaking up into smaller groups with 30-40 nests each.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Foraging Great Blue Herons are not hard to find in appropriate habitat throughout the year. Some prominent rookeries can be found on Samish Island between Samish Bay and Padilla Bay (Skagit County); at the Dumas Bay Sanctuary in Tacoma (Pierce County); by the Ballard Locks in Seattle, at Lake Sammamish State Park (both in King County); on Vancouver Lake (Clark County); and at Potholes WRA (Grant County). When observing Great Blue Heron rookeries, please keep in mind the 1000-foot disturbance buffer zone.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| North Cascades | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| West Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| East Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Okanogan | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | F | F | U | U |

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Blue Mountains | R | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | U | R | R | |

| Columbia Plateau | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map