Dunlin

General Description

This small shorebird is distinctive in breeding plumage, with a black belly-patch extending behind its black legs. Its head and breast are light-colored, and its back is bright rufous. In non-breeding plumage it is drab gray with a brownish head and breast. In flight it has white underwings, a white line down the middle of the upperwing, and white on either side of its rump and tail. The white underwings are especially distinctive in flight. As a flock twists and turns together in flight, white flashes of underwing are evident from a distance.

Habitat

Tundra-breeders, Dunlin typically nest in wet meadow tundra with low ridges, vegetation hummocks, and nearby ponds. During migration and winter, they prefer mudflats, but can also be seen on sandy beaches, coastal grasslands, estuaries, and occasionally in muddy, freshwater areas.

Behavior

Dunlin flocks are often huge, most impressive when they display their coordinated aerial maneuvers trying to escape predation by Peregrine Falcons and Merlins. When foraging, they either pick food from the surface or probe in the mud. They feed on exposed mud or in shallow water, making short runs interspersed with periods of feeding. They feed day or night, depending on the timing of low tide.

Diet

On the breeding grounds, insects and insect larvae are the most important source of food. In coastal habitats, Dunlin also eat marine worms, small crustaceans, mollusks, and other aquatic creatures. They sometimes eat seeds and leaves.

Nesting

Males typically arrive first on the breeding grounds. Pairs form when females arrive, but if arrival on the breeding grounds is delayed due to weather, pairs may form prior to arrival. Former mates often use the same territory as in the previous year. The male starts a few scrapes, which may be lined with grass, sedge, and willow leaves. The female chooses one and finishes the construction. The nest is usually well hidden under a clump of grass or on a hummock. Both parents incubate the four eggs for 20 to 22 days. The young leave the nest shortly after hatching and find their own food. Both parents tend the young, although the female usually abandons the group within a week of hatching. The male generally stays with the young until they are close to fledging, typically about 19 days.

Migration Status

Dunlin molt before they start the southward migration in the fall, and adults and juveniles migrate at generally the same time. Late-fall migrants, they are some of the last shorebirds to leave their wintering grounds. They are short- to medium-distance migrants, and travel from the low Arctic or sub-Arctic to temperate coastal areas in North America, and rarely as far as Central America. Juvenile plumage is seldom seen in Washington, although some birds in juvenile plumage (molting) can be seen in the eastern flyway.

Conservation Status

The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the Dunlin population at 3,934,000 birds worldwide, with 1,325,000 in North America. Of that group, 500,000 birds make up the Pacific Coast population. Dunlin are currently the second most common shorebird in Washington, and the most common of Washington's wintering shorebirds, but numbers have declined in the Northwest in recent decades. There has been little habitat destruction or disturbance on the breeding grounds to date, but the migration and wintering grounds are threatened by destruction of habitat. There is currently no reliable information about population status or trends for Dunlin range-wide, so it is unknown if the trend in the Northwest is due to a decrease in population or a shift in range. Dunlin are considered an indicator species for assessing the health of Holarctic ecosystems, so determining range-wide population trends should be of high priority as reduction in their numbers could indicate that other species that use these ecosystems are at risk.

When and Where to Find in Washington

On the coast, Dunlin are rare throughout the summer. Fall migrants start showing up at the end of September. By October, they are common, and remain common through mid-May. Numbers peak at the end of March into April, as birds that wintered farther south join Washington's wintering birds before heading to the breeding grounds. By the end of May they are rare. They can be found in all the large coastal bays, but are usually patchily distributed, with thousands of birds in one spot, and none in a nearby, seemingly comparable area. Large flocks can usually be found, however, in Bellingham Bay (Whatcom County), Skagit Bay (Skagit County), Grays Harbor (Grays Harbor County), Willapa Bay (Pacific County), and the Columbia River Estuary (Pacific County). Most of these areas support flocks of 5,000 or more throughout the winter. The flock in Grays Harbor averages about 30,000 birds, with numbers much higher on occasion. Dunlin can also be seen in smaller flocks throughout the Puget Trough in winter. They are uncommon in eastern Washington during migration, with more moving through that region in the spring (from mid-April to mid-May) than fall (October). Small numbers also winter in eastern Washington, particularly at the Walla Walla and Yakima River deltas.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | C | C | C | C | C | R | R | R | U | C | C | C |

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | C | F | R | R | R | C | C | C | |

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | U | F | F | U | F | F | F |

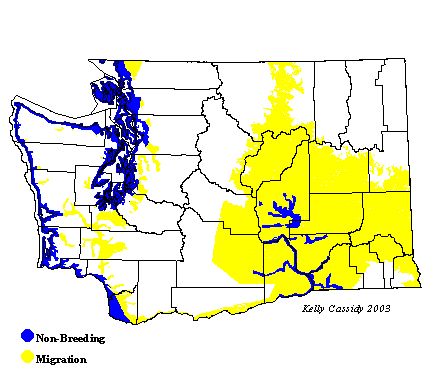

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius