Pectoral Sandpiper

General Description

Described as a larger version of a Least Sandpiper, the Pectoral Sandpiper is a medium-sized shorebird with a heavily streaked breast, sharply contrasting clear, white belly, and yellowish legs. The bill droops and is black at the tip, and lighter brown at the base. In flight, the tail shows a dark stripe down the middle, with white on either side. The upper wing has a very narrow stripe. Males are larger than females, and males have inflatable sacs in their breasts, used in courtship.

Habitat

Pectoral Sandpipers breed all across the North American Arctic and across northern Siberia at the dry edges of well-vegetated wetlands. During migration, they can be found in fresh- and saltwater marshes, on mudflats, or drying lakes and wet meadows. They winter in South American grasslands.

Behavior

Pectoral Sandpipers move along steadily with their heads down, picking up prey on the surface and probing lightly into the sand or mud. They usually forage in vegetation, and when they are disturbed, they stand upright with their necks extended, peering over the grass.

Diet

During the breeding season, Pectoral Sandpipers eat flies and fly larvae, spiders, and seeds. During migration, they eat small crustaceans and other aquatic invertebrates, although insects may still be the major food.

Nesting

Pectoral Sandpipers are promiscuous: males mate with multiple females, and females mate with multiple males. Males arrive on the breeding grounds before females and establish territories. When females arrive, the males attract them with a flight display, rhythmically expanding and contracting the air sacs in their breasts. The female builds a nest in a grassy spot on the ground, often on a slightly elevated spot. The nest is usually a well-hidden scrape lined with grass and leaves, sometimes under low shrubs. She provides all the parental care. Incubation lasts for 21 to 23 days, and the four chicks leave the nest and feed themselves soon after hatching. The female stays with the young for about 10 to 20 days. The young start to fly at around 21 days, and are capable flyers by 30 days.

Migration Status

Extreme long-distance migrants, some Pectoral Sandpipers make an 18,000-mile round-trip journey between breeding and wintering grounds. The birds that migrate through Washington most likely breed in Siberia and migrate across the Bering Strait and down the Pacific Coast. They winter in southern South America, Australia, and New Zealand.

Conservation Status

The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the population of Pectoral Sandpipers at 400,000 birds, with about half that number breeding in North America. Historical reports of enormous numbers along migratory corridors indicate that the population is not what it once was. While hunting may have had an impact in the late 1800s and early 1900s, habitat destruction is currently the most significant threat. There is not a lot of reliable information on population trends of this species, and more data would be helpful. However at this point, the Pectoral Sandpiper is not classified as a species in need of high-priority conservation.

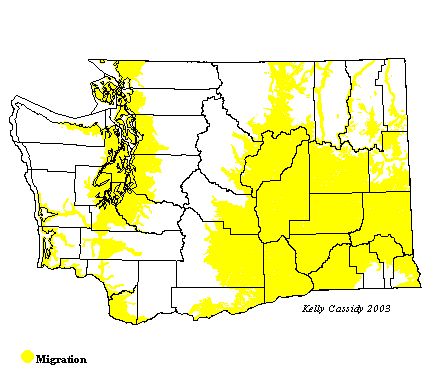

When and Where to Find in Washington

Migrants are much more common in Washington in fall than spring. Fall visitors start showing up in the interior in small numbers in late June. Their numbers increase into July and August, and by mid-August they are common. By late October, numbers start tapering off. They are uncommon by the end of October, and rare through most of November. Coastal birds start arriving in mid-July, but are uncommon through mid-August. From mid-August to October, they are common, then become uncommon again through early November. A few stragglers can sometimes be seen through the end of November. Most of these birds are juvenile.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | F | F | R | ||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | U | F | U | ||||||

| North Cascades | R | R | R | |||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | U | F | U | |||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | F | F | |||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R | U | F | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius