Loggerhead Shrike

General Description

This medium-sized, gray songbird is the smaller and darker of the two species of shrike in North America. The Loggerhead Shrike has a gray underside and a darker gray back. Its wings are black with white patches, and its tail is black with white corners. Its head is large in proportion to its body. It has a heavy bill that is hooked at the very tip, and a wide black mask across its face. Juveniles are browner than adults, with buffy wing-bars and barred underparts. Loggerhead Shrikes have a shorter bill and a broader mask than Northern Shrikes. Their cheeks are brighter white, giving more contrast to their facial pattern. For the most part, the two species are found in Washington at different times of year, but they do overlap in some places.

Habitat

Loggerhead Shrikes are found only in North America. They breed in open country, including grasslands and shrub-steppe areas, where there are scattered trees, tall shrubs, fence posts, utility wires, or other lookout posts. They tend to nest in northeast- or southeast-facing ravines. Loggerhead Shrikes prefer more open country than that preferred by Northern Shrikes.

Behavior

Loggerhead Shrikes need large territories and thus are found only in low densities. They hunt by watching from high perches, then flying swiftly down after prey. Shrikes use their hooked bills to break the necks of vertebrate prey. Because their feet are not large or strong enough to hold prey, shrikes find a crotch in a tree, a thorn, or barbed wire to hang their prey on while they eat. Prey may be left on such a site for later consumption.

Diet

The Loggerhead Shrike is predominantly an insect-eater, especially in the summer when it feeds largely on grasshoppers. It also occasionally eats small lizards, rodents, and small birds.

Nesting

Loggerhead Shrikes nest in dense, thorny trees or shrubs, brush-piles, and even tumbleweeds. In Washington, they prefer tall, dense shrubs, usually in ravines. During courtship, the male makes short display flights and feeds the female. Both sexes help find the nest site and gather materials, but the female builds the nest, which is a bulky cup of twigs, grass, weeds, and bark lined with rootlets, hair, and feathers. The female incubates 5-6 eggs for 15-17 days, and then broods the young for the first 4-5 days after they hatch. The male brings food to the female and the young during this time. After this initial period, both parents feed the young, which leave the nest at 17-20 days and start to fly about a week later. The parents continue to feed and tend the young for another 3-4 weeks.

Migration Status

Loggerhead Shrikes winter primarily in the southern US. Many winter in the Central Valley of California, and also along the Texas coast. They usually arrive in Washington in mid-March and leave by mid-September, although a very few birds winter here. Those that do migrate are short- to medium-distance migrants.

Conservation Status

The numbers of Loggerhead Shrikes have declined across North America, for reasons that are not well understood. The decline has been extreme in the northeastern US, and they are considered extirpated from New England. The US Fish and Wildlife Service currently lists it as a species of concern. It is a candidate for listing by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and is considered an at-risk species by the Washington Gap Analysis Project. While the Breeding Bird Survey has not found significant declines in Washington, there have been non-significant declines, and the Loggerhead's decline throughout the rest of its range is of concern in Washington. It is considered an important indicator-species for the health of the shrub-steppe ecosystem, which has undergone major destruction and alteration. Protection of habitat and reduction of pesticide use should both be implemented to stem this decline, while more research is done to understand it more fully.

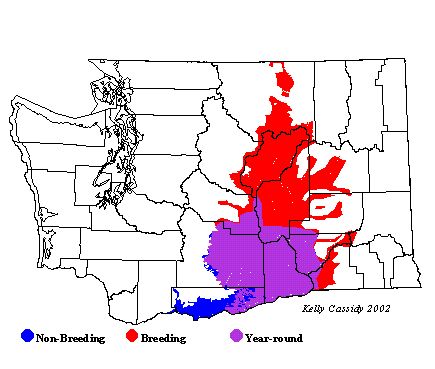

When and Where to Find in Washington

A few wintering birds can be found in most years in the Columbia River bottoms east to the Tri-Cities area, and occasionally but rarely in western Washington. They are mostly summer visitors, however, and are usually common in eastern Washington from mid-March to mid-September. They commonly nest at Hanford (Benton County), at the Yakima Training Center and Toppenish National Wildlife Refuge (Yakima County), along the Colville Plateau and east of Tonasket (Okanogan County), as well as in other areas of appropriate habitat in eastern Washington. The Loggerhead Shrike is rarely seen in Washington during the winter.

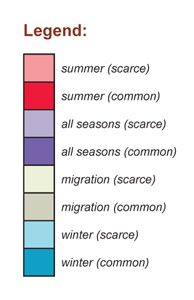

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | ||||||||||||

| Puget Trough | ||||||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | |||||

| Okanogan | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map