Whimbrel

General Description

Whimbrels are large shorebirds with long, decurved bills. They are smaller in size than the similar-looking Long-billed Curlew, and their bills are shorter. The Whimbrel has a distinct head pattern, with dark-and-light alternating stripes. The rest of its plumage is plain mottled-brown overall, and does not vary season to season. In flight, it appears brown all over, with a white belly. Its bill is solid black in summer and has a pinkish or reddish base during winter.

Habitat

Whimbrels nest in the tundra, not far from the tree line, in a variety of open habitats from wet lowlands to dry uplands. During migration, they use wetlands, dry, short grasslands, farmland (especially plowed fields), and rocky shores. During winter, they are mostly found in coastal areas, on exposed reefs, sandy or rocky beaches, estuaries, and especially mudflats.

Behavior

In spring, Whimbrels may congregate in farmlands in groups of up to several hundred. They probe into the mud for their food, and pick food from the surface more often than do other curlews. Whimbrels feed singly or in small groups on mudflats at low tide. Then at high tide, they gather and roost in dense flocks, often flying long distances between roosting and feeding areas.

Diet

During breeding season, Whimbrels eat primarily insects. Later in summer, they also eat berries. Their migration and wintering diet consists of worms and grubs, crabs, and other small aquatic organisms. Fiddler Crabs are an important food during winter, and the shape of the Whimbrel's bill matches the curve of the crab's burrow.

Nesting

These monogamous birds nest in loose colonies, but remain territorial during the nesting season. Males use dramatic flight displays and songs to attract females. They nest on the ground, usually in a raised hummock or at the base of a small shrub. The female generally builds the nest, which is a shallow scrape lined with lichen, leaves, moss, or grass. Both parents help incubate the 4 eggs for 24-28 days. The young leave the nest soon after hatching and feed themselves. Both parents tend and defend the young, although the female generally leaves the brood first, and the male stays with them until they can fly, at 4-6 weeks.

Migration Status

Adults leave the nesting grounds in July, and the young of the year typically follow a month later. Whimbrels are commonly found inland during migration, although they winter coastally. During migration, the population tends to congregate at a few favored spots. The population breeding in North America winters along the Pacific Coast, from southern Oregon to the southern tip of South America. The birds travel northward from March through May.

Conservation Status

Whimbrels breed around the world at high northern latitudes. The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the worldwide population at 797,000 birds and the North American population at 57,000. They have a widespread range and can be found on the coasts of six continents in the winter. Hunting in the 19th Century reduced the population. The ban on hunting in North America has resulted in a population rebound, but apparently not back to historic levels. While they are still being hunted for food in parts of South America, Whimbrels are now more seriously threatened by habitat destruction, disturbance, and environmental contaminants. The Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network is working to identify and protect important shorebird wintering and migration stopover areas, and this may help to protect Whimbrels. The current population trend is uncertain, and more monitoring is needed to understand their current status.

When and Where to Find in Washington

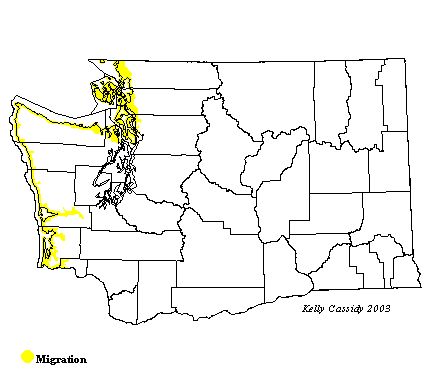

Whimbrels are seen in Washington mostly during migration, but there are a few winter records from the coast. Some non-breeding birds summer on the coast as well. Migrating birds start coming through the Washington outer coast and Puget Sound in early April, are common from mid-April through mid-May, and then taper off through the end of May. The southward migration starts in late June, and they are common on the coast through mid-August. After this, they taper off and are uncommon until the end of October. In eastern Washington, migrating Whimbrels are fairly rare, but can be seen from mid-April to early June, and then again from late June through the end of August. They are more likely to be seen on the trip north than on the trip south. In western Washington, they are more common in spring in the protected waters of Puget Sound and the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Fall migrants are more likely to be found in coastal estuaries such as Grays Harbor (Grays Harbor County) and Willapa Bay (Pacific County), although they do occur along inland marine waters as well.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | F | C | U | U | F | F | U | R | R |

| Puget Trough | U | U | R | U | U | R | ||||||

| North Cascades | R | |||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius