Western Kingbird

General Description

Except for the Tropical Kingbird (a rare visitor in fall), the Western Kingbird is the largest flycatcher in Washington. It is light gray-green above with darker wings and a black tail with white outer edges. Its breast is light gray, and its belly and underwings are bright yellow. It has red feathers in its crown that can be seen only when it displays.

Habitat

Western Kingbirds inhabit open areas with scattered trees or utility poles for nesting. They are especially common around ranch buildings and corrals where perches are plentiful.

Behavior

Aggressive and conspicuous, Western Kingbirds can easily be found perching on fence wires all over eastern Washington. They wait on these perches and then make quick flights out to grab prey from the air or off the ground. They commonly hover over a field and then drop to the ground after prey.

Diet

Insects, both flying and crawling, make up the majority of the Western Kingbird's diet. The birds also eat small berries and other fruit.

Nesting

In Washington, Western Kingbirds usually nest in a Ponderosa pine or on a utility pole next to a transformer. They also nest on building ledges, in sheds, or in other birds' nests. Unlike Eastern Kingbirds, they do not need water nearby to nest. Monogamous pairs are formed after the male performs an elaborate display flight, twisting and flipping through the air. The female builds a cup of grass, weeds, twigs, and plant fibers, and lines it with feathers, plant down, and hair. She incubates three to four eggs for about two weeks. Both parents feed the young, which leave the nest at 16 to 17 days. The parents continue to feed the young for another two to three weeks.

Migration Status

Western Kingbirds usually arrive in Washington in late April or early May. They leave for southern Mexico and Central America in August, traveling alone or in small flocks.

Conservation Status

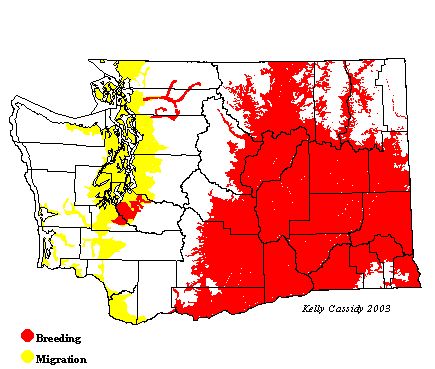

Western Kingbirds are more widespread across eastern Washington than Eastern Kingbirds because, unlike Eastern Kingbirds, they are not restricted to areas near water. They have adjusted well to increased development in their breeding habitat, making use of man-made structures for perching and nesting. During the 20th Century, they expanded their range eastward and have increased in number across much of their range, including Washington. At one time they were more common in western Washington, but numbers have declined as the prairie habitat has disappeared. Pesticides are a concern across much of their range and have been detected in the blood of many Western Kingbirds. However there have been no signs of eggshell thinning. The Breeding Bird Survey shows a small, not statistically significant decline in Washington between 1980 and 2002.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Western Kingbirds are common from May to August in the open lowlands of eastern Washington, especially in farmland. In western Washington, they are rare breeders, with breeding confirmed in Pierce, Skagit, and Whatcom Counties. Migrants can also be seen rarely throughout western Washington including the outer coast during the spring and fall.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | ||||||||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| North Cascades | R | R | R | |||||||||

| West Cascades | R | R | R | |||||||||

| East Cascades | R | U | U | U | U | R | ||||||

| Okanogan | U | C | C | C | U | |||||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | U | U | U | U | |||||||

| Blue Mountains | U | U | U | U | U | |||||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | C | C | C | F | R |

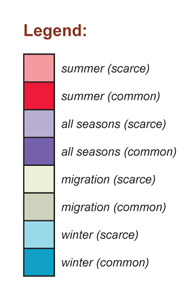

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Olive-sided FlycatcherContopus cooperi

Olive-sided FlycatcherContopus cooperi Western Wood-PeweeContopus sordidulus

Western Wood-PeweeContopus sordidulus Alder FlycatcherEmpidonax alnorum

Alder FlycatcherEmpidonax alnorum Willow FlycatcherEmpidonax traillii

Willow FlycatcherEmpidonax traillii Least FlycatcherEmpidonax minimus

Least FlycatcherEmpidonax minimus Hammond's FlycatcherEmpidonax hammondii

Hammond's FlycatcherEmpidonax hammondii Gray FlycatcherEmpidonax wrightii

Gray FlycatcherEmpidonax wrightii Dusky FlycatcherEmpidonax oberholseri

Dusky FlycatcherEmpidonax oberholseri Western FlycatcherEmpidonax difficilis

Western FlycatcherEmpidonax difficilis Black PhoebeSayornis nigricans

Black PhoebeSayornis nigricans Eastern PhoebeSayornis phoebe

Eastern PhoebeSayornis phoebe Say's PhoebeSayornis saya

Say's PhoebeSayornis saya Vermilion FlycatcherPyrocephalus rubinus

Vermilion FlycatcherPyrocephalus rubinus Ash-throated FlycatcherMyiarchus cinerascens

Ash-throated FlycatcherMyiarchus cinerascens Tropical KingbirdTyrannus melancholicus

Tropical KingbirdTyrannus melancholicus Western KingbirdTyrannus verticalis

Western KingbirdTyrannus verticalis Eastern KingbirdTyrannus tyrannus

Eastern KingbirdTyrannus tyrannus Scissor-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus forficatus

Scissor-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus forficatus Fork-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus savana

Fork-tailed FlycatcherTyrannus savana